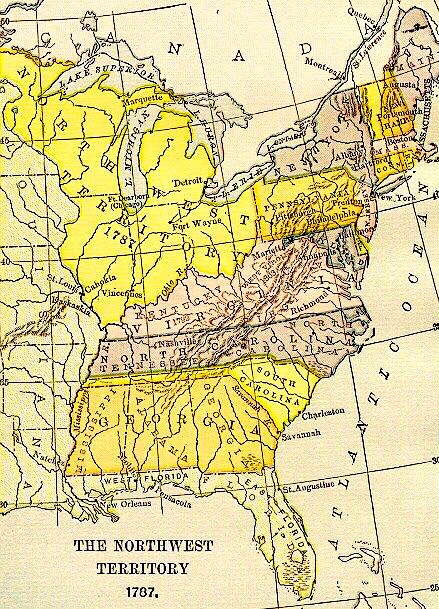

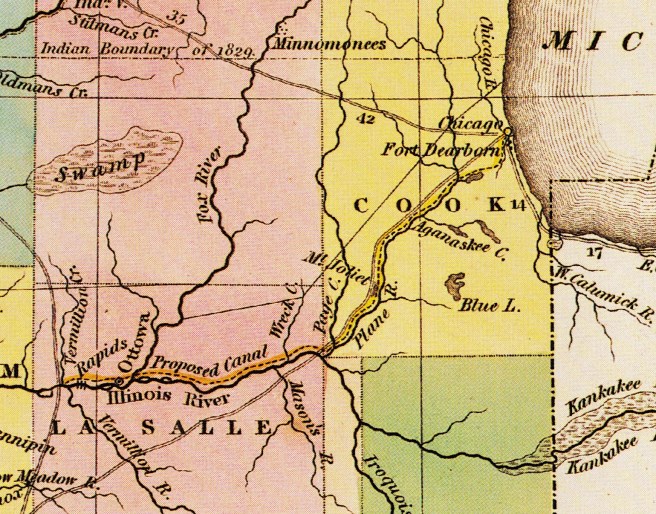

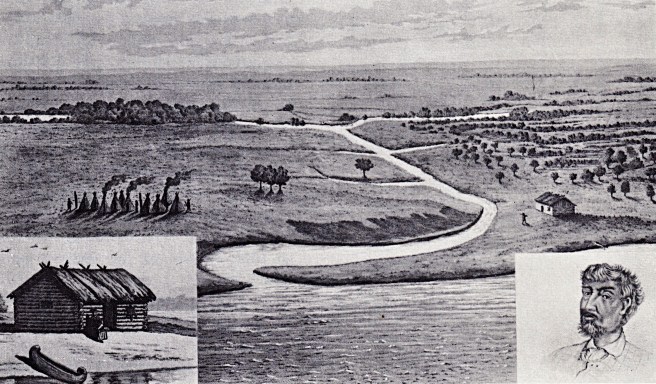

Meanwhile, the newly created state of Illinois wasted little time in initiating plans for the Chicago canal’s construction. The governor of the new state, Shadrack Bond, ordered the first survey of the strip of land previously ceded by the Natives in 1816, and in June 1821 Surveyor John Walls surveyed Township 39 North of the baseline, Range 14 East of the Third Principal Meridian imposing the geometric rigor of the 1785 Land Ordinance onto the virgin prairie along the Chicago River. Gov. Bond also proposed that some of the proceeds from the sale of lands set aside by the Federal Enabling Act for the construction of roads be diverted to help pay for the canal. Consequently, Illinois Senator Jesse B. Thomas and Congressman Daniel P. Cook set out to secure the support of the Federal government for this endeavor. Their initial labors achieved a modicum of success when Congress voted on March 30, 1822, to give the state permission to dig the canal on Federal property.

More importantly, however meager it may have appeared, Congress not only voted $10,000 to pay for the surveys already begun, but also donated a strip of land comprising ninety feet on each side of the proposed route as well as all material (timber, etc.) on the adjacent public land. Congress had set the precedent for granting former lands of the Native tribes to the states to fund internal improvements some twenty years earlier in 1802, when it gave “public lands” in Ohio to finance the construction of roads. Thus encouraged, the Illinois House established on February 14, 1823, a canal commission to complete the surveys and prepare an estimate of the cost to construct the canal. Undoubtedly encouraged by the imminent completion of the Erie Canal scheduled for October 1825, the Illinois & Michigan Canal Company was optimistically incorporated on January 17, 1825, with stock initially valued at $1 million. Sufficient private capital, however, was not willingly committed to such a long-term venture, so the legislature annulled the company a year later. Pressure then began to build on the State, however, to start construction on its canal, so the state, following the highly-contentious Presidential election of 1824 that saw the election of Massachusetts’ John Quincy Adams, over Andrew Jackson by a single vote in a run-off election in the House of Representatives, who was more predisposed to internal improvements than had been the Virginians Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe, Illinois sent Cook back to Washington, hoping to increase the Federal government’s investment in the canal.

Once back in Washington in 1826, Cook was able to use the completion of the Erie Canal in the previous October to aid his argument. The Erie Canal’s Grand Celebration on October 26, had begun with a successive cannonade by canons placed within earshot of each other starting at Buffalo along the entire length the Canal and down the Hudson River to New York City and back. The “Grand Salute” took three hours and twenty minutes. Meanwhile a flotilla of canal boats, led by Gov. Clinton aboard the Seneca Chief, departed on a ten-day trip to New York City, where Clinton ceremonious poured a keg of Lake Erie water into New York Harbor, consummating the “Wedding of the Waters.”

Cook pursued Federal funding for the Chicago canal claiming that it was an issue of national, and not merely regional importance due to its potential ability to facilitate troop and supply movements during wartime, citing the now completed Erie Canal. Illinois’ political hunch to approach the new Congress and President paid off as the constitutional logjam over the role of the Federal government in Internal Improvements was broken by Adams with his goal of a national system of transportation and communications. (If Jackson had won the election, it is quite conceivable, based on his later record on internal improvements, that the canal would have remained still-born for the better part of what would have been Jackson’s eight year term. Therefore, Adams’ election was critical to the founding of Chicago, for without the 1827 landgrant, there would have been no funding for the canal, let alone the surveys needed to sell the real estate at the mouth of the river.)

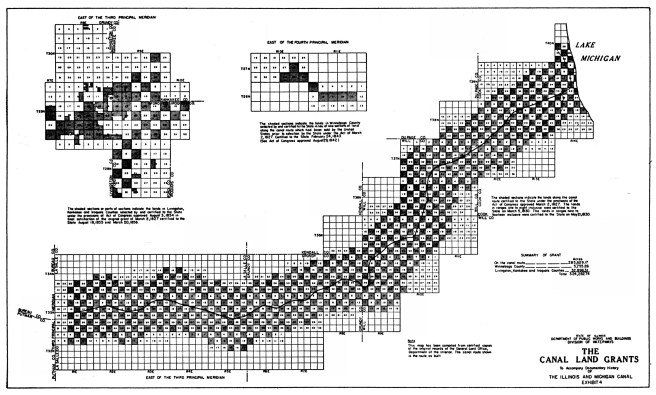

On March 2, 1827, Congress approved a landgrant to Illinois consisting of the original landgrant, as well as the alternate five sections (commonly referred to as the “checkerboard system”) within a ten-section width that followed the canal’s route. The sale of this land that totaled in excess of 284,000 acres (the equivalent of a width of five square miles along the path of the canal), was intended to help finance the construction of the Chicago canal. The plan was quite straightforward. The state would first sell the land in its sections to private citizens, in order to generate funds to pay for the canal’s construction, while the Federal government held onto its alternating sections for sale at a later date. Theoretically, the construction of the canal and the corresponding improvements made in the state’s sections would increase the value of the Federal holdings, so that when these were sold, the Federal government would recoup the cost of the initial giveaway to the state.

1.14. THE DEMOCRATS TAKE CONTROL: ANDREW JACKSON AND MARTIN VAN BUREN

While one could credit Pres. Adams’ support for internal improvements as having encouraged these early efforts to build a network of roads and canals throughout the country, his involvement was to be short-lived as Jackson, who approached the 1828 election as a duel to regain his lost honor after the 1824 election, easily defeated Adams’ reelection bid. The 1828 election marked the end of the unity of the “Era of Good Feelings” as the Democratic-Republican Party of Thomas Jefferson split between those who backed Adams, who eventually were referred to as “National Republicans,” and those who supported Jackson, who eventually dropped the word Republican from their party, preferring to known as “Democrats.”

As Jackson mounted his campaign to challenge Adams’ reelection in 1828, he was courted by then Gov. DeWitt Clinton and Sen. Martin Van Buren, the leaders of the two factions of the most influential state political party in the North, New York’s Democratic-Republican Party. Martin Van Buren (note: he will be responsible for the most impact on Chicago’s early growth) had been born in Kinderhook, NY, just south of Albany, and after having finished his law studies, had gravitated to New York State politics in Albany, a field for which his innate talents of genial conversation and perpetual scheming would serve him well. Following DeWitt Clinton’s election in 1813 as the Mayor of New York, coming after his unsuccessful bid to oust Pres. Madison, Van Buren had joined the “Opposition Party,” the Albany faction of New York State’s Democratic-Republican Party who opposed Clinton’s faction (whose power base was in “downstate” New York City). Following Clinton’s election as Governor on July 1, 1817, Van Buren had formed the “Bucktail” faction of the party, in conjunction with and modeled after New York City’s Tammany Hall, the original target of Mayor Clinton’s political reforms, (Van Buren had even chosen Tammany’s symbol, a deer’s tail worn in one’s hat, as the new group’s symbol.) to oppose Gov. Clinton’s control of the party and its patronage throughout the state. Van Buren used the new organization to leapfrog over Clinton onto the national political stage with his election to the U. S. Senate in late 1820. In order to oust Clinton as Governor, Van Buren then formed and became the leader of the “Albany Regency,” one of America’s early political machines that ran the state’s Democratic-Republican politics through tight organization and by controlling the patronage that flowed from the New York State Capitol. Meanwhile in the U.S. Senate, Van Buren had matured in national politics, where he became acquainted with Gen. Jackson following his election as Tennessee’s Senator in 1822.

Following Jackson’s unsuccessful 1824 Presidential campaign, Van Buren had joined forces with Adams’ Vice-President John C. Calhoun, who eventually also became opposed to Adams, and privately had advanced Calhoun’s interest in being named as Jackson’s Vice-President in the coming 1828 election as a means of blunting his nemesis Clinton’s chances of becoming Vice-President. Clinton, having already run a Presidential campaign, appears to have had the inside track within the Jackson campaign, but unfortunately, suddenly died at the relatively young age of fifty-eight on Feb. 11, 1828, leaving Van Buren, the “Little Magician” who saw partisan politics as a game to win, to be the architect for Jackson’s campaign, and thus, expanded the Albany Regency’s “machine politics” onto the national stage. Following Jackson’s election in 1828 as President and Calhoun’s re-election as Vice-President, Jackson named Van Buren as his Secretary of State. As we will see, if Clinton had lived, his influence on Jackson might have swayed the President’s mind to a more “nationalistic” view of the need for Federal internal improvements, similar to Clinton’s Erie Canal, that could have resulted in a better organized national system of transportation that could have cemented St. Louis’ role as the center of the West. With Van Buren advising Jackson, internal improvements would be approved in a rather ad hoc manner along the lines of political expediency with little, if any centralized planning that over time would work to the long-term benefit of Chicago. The ripples of Van Buren’s growing influence and power would soon impact the mouth of the Chicago River…

Further reading:

Andreas, Alfred T. History of Chicago, 3 vols. Chicago, 1884-1886. Reprint, New York: Arno Press, 1975.

Harpster, Jack. A Biography of William B. Ogden. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University, 2009.

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)