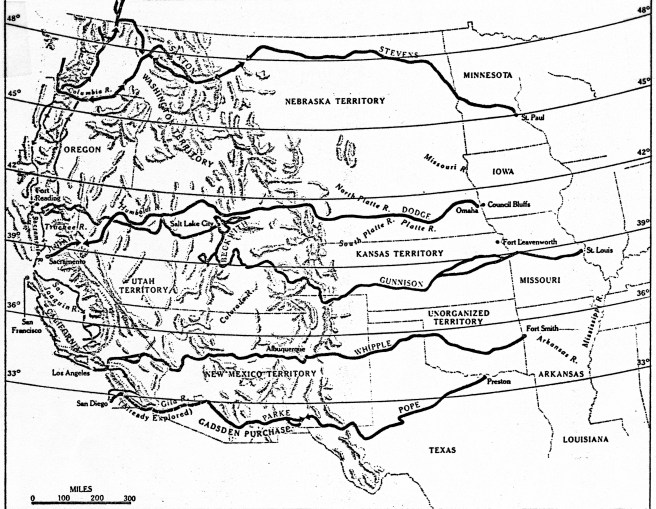

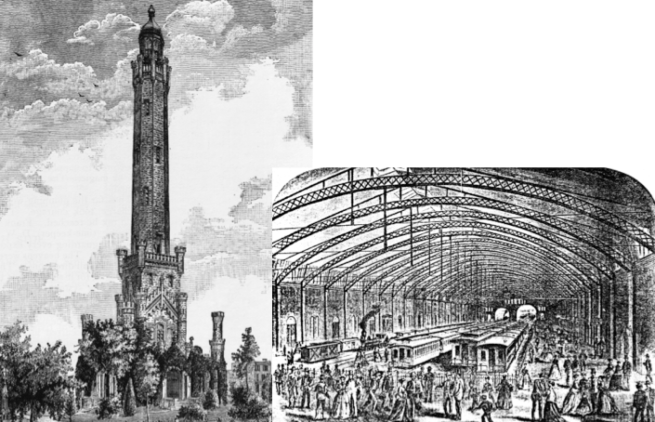

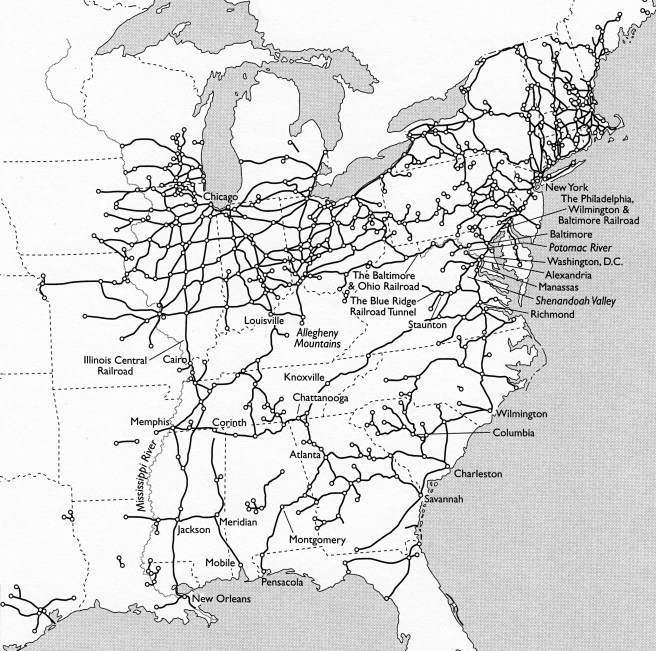

What I have attempted in this blog is to set the history of Chicago and its architecture of this period within its historical context. To truly understand and appreciate what an architect was trying to do in the design of a building, it is essential to know the surrounding physical context of the building’s site: which direction is south, what types of streets border it, and what existing buildings are immediate adjacent to it. A building’s “context,” however, is broader than just its site, as it includes the efforts of all of the people involved and the corresponding forces, decisions, and pressures addressed, and many times overcome, in the creation of the building. In the previous three paragraphs I purposefully referenced some of the leading European architectural theorists of the era without introducing them. These were the leading writers of modern architectural theory at the time, whose books were read, studied, and discussed by architects in Europe and the U.S., including Chicago. Chicago was not an island onto itself, isolated at the edge of civilization from any influence from developments or buildings in other cities or countries: it was intimately linked to the rest of the country by the telegraph and railroad. Within the short span of twenty-three years after its founding in 1833, Chicago had gone from being on the fringe of civilization, to being the center of American Midwestern civilization in 1856 as it became the hub of the largest network of tracks in the world.

The development of a city is no different from that of its architecture. Chicago did not grow in a vacuum; it was impacted by seemingly unrelated events that sometimes took place in remote locations. This was the context in which Chicago and its architecture evolved, and therefore, to get a clear and thorough understanding of the development of the city, including its architecture, one should examine the context in all its relevant aspects in which these events unfolded. For me, context is everything. In my forty-plus years of teaching architectural history at the University of Cincinnati to majors and non-majors alike, I found that not only introducing students to the topic, but also by placing the topic within its context, be that the historical, economic, social, political, geographic, or artistic context, at the regional, national, or international scale, gave a student a fuller understanding and appreciation for the topic. This is what I have attempted to do in this blog. I also recognize that a large portion of my audience is not intimate with many of the details of history that I need to refer to in telling this story. Therefore, I found it important to include sections that included events, people, and buildings from cities beyond Chicago and to summarize topics beyond those that directly relate to Chicago that I believe a reader needs to know in order to better comprehend a particular topic’s context. For those who already know the history of any of these topics that I have included, such as Napoleon III’s urban renewal of Paris or the British Design Reform movement, they can simply skip over the posts so dedicated if one wishes. But those who are not familiar with such topics will find their understanding of the topic to be richer for having been introduced to the contextual information.

The four most important cities that played pivotal roles in Chicago’s historical, urban, and architectural development, that one cannot ignore if one wants to truly understand the Chicago phenomenon were Paris, London, Cincinnati, and New York. During the Second Empire of Napoléon III, Paris, la ville lumiére, had become the most important city in the world for both its architecture and its urban design, as the Emperor had embarked upon a twenty-plus year campaign to bring his capital into the technological nineteenth century. No less than French novelist, Victor Hugo, no fan of the Emperor by the way, sang the city’s praise best:

“It is in Paris that the beating of Europe’s heart is felt. Paris is the city of cities. Paris is the city of men. There has been an Athens, there has been a Rome, and there is a Paris…”

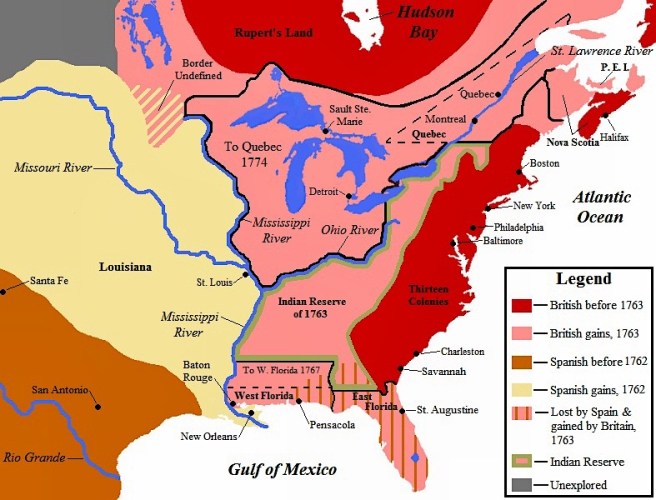

Napoléon III’s Paris was the model city for almost everyone who wanted to build a beautiful city in the later half of the nineteenth century. As we will see, there was a curious parallel in the chronology of events between the rise of the Second Empire of Napoléon III and the rise of Chicago (let’s not forget that the first European explorers of the Chicago area who laid claim to the region were French), starting with the timing of Louis Napoléon’s rise in French politics during the summer and fall of 1848, when he won the highest number of the votes cast for the National Assembly on September 17-8, that led to his victory in the Presidential election some three months later on December 10-11. As Louis Napoléon had spent the summer of 1848 laying the foundation for his eventual political success, William Ogden had spent that same summer laying the first tracks for the Galena & Chicago Union railroad (that would ultimately bring the transcontinental railroad to Chicago), with its first official run of eight miles having taken place on Nov. 20, only twenty days before Louis Napoléon was elected President. Meanwhile, at the end of this blog’s timeframe, one cannot fully comprehend the fear personally felt by Chicago’s “leading citizens” following the city’s destruction by the 1871 fire without understanding that some of Paris’ most important buildings had been destroyed only four and a half months earlier by fires purposefully set by members of the Parisian Commune (Communards) and that over 20,000 Parisians had been killed, as the army of the Nationalist government crushed their three-month long revolt and regained control of the city during the week of May 21-28, 1871.

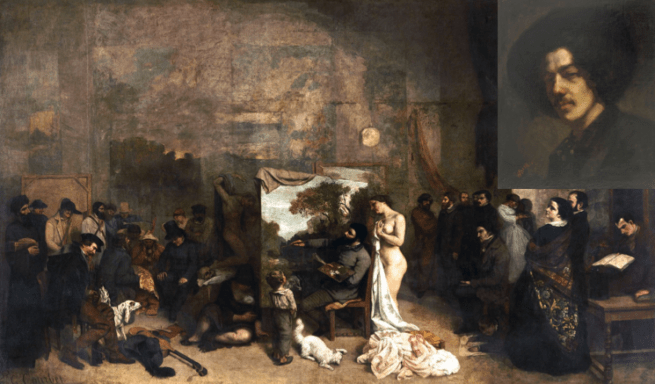

London at this time offered an artistic alternative in European design theory to that of Paris. So much so, in fact, that it will become quite evident to the reader that American architecture will be pulled between these two primary European poles of design theory during the second half of the nineteenth century. The battle within American architecture during this era was waged between those who championed the academic Neo-Baroque eclectic architecture of the Second Empire, and the few, but growing number of individuals who were influenced by the rising tide of innovative design initiated by the British writers Jones, Pugin, and Ruskin. It was of no little consequence that the most important buildings under construction in Europe between 1848 and 1871 that were most emulated by American architects were the Tuileries/Louvre complex and the Opera House in Paris, the Oxford Museum and the Midland Hotel/St. Pancras Station in London, and, of course, the Doge’s Palace in Venice that Ruskin had posited as “the central building of the world.”

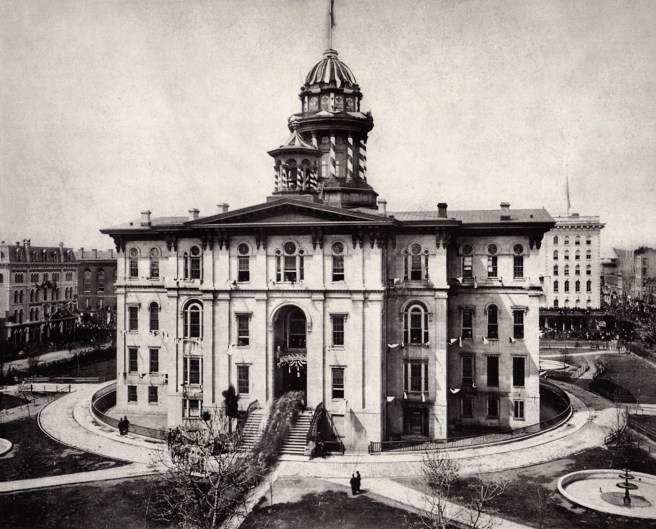

When Chicago was chartered as a town on Aug. 5, 1833, it had little in the way of indigenous cultural traditions and institutions, including architecture. When it was eventually ready to invest in these, Chicago naturally looked eastward for inspiration and precedents. The closest competition that Chicago had to overcome was that of Cincinnati, the “Queen City of the West.” Having had a forty-five year head start, Cincinnati had already moved beyond mere survival and into the cultural phase of urban development before Chicago had even been chartered as a city in 1837. As the two cities were basically in the same geographic region, it was Cincinnati, and not New York City, as is so often presumed to have been the case, that provided Chicago with models for it to first emulate when it was finally interested and financially able, and then to surpass those of its older and more established Midwestern competitor. But once Chicago had equaled Cincinnati, it then set its sights on New York City, the most important American city in regard to mid-century architecture. As New York was the largest city by population and economic importance in the U.S., it simply follows that New York’s architecture (especially that designed by George Post), modeled often, but not solely after Paris and London, would play a leading role within the country, even in Chicago.

i.8. SUMMARY

I have chronologically organized this study into five parts:

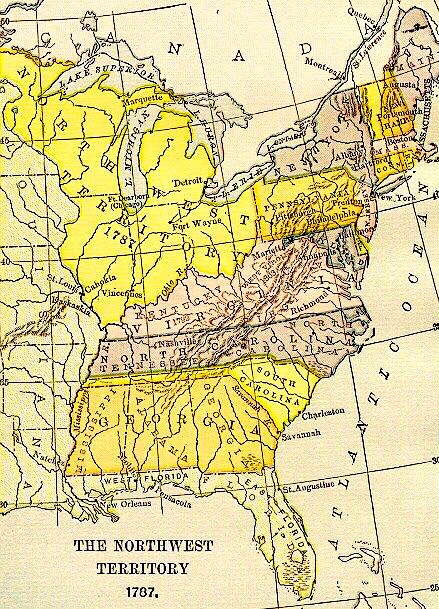

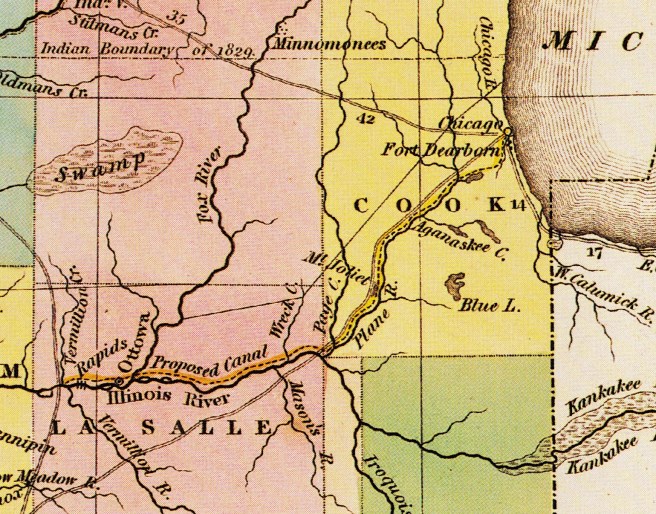

1. the period from the first French claim on “Louisiana” that included the Chicago River in 1671 to the completion of the Illinois & Michigan Canal in 1848;

2. the period from when William Ogden began construction of the Galena & Chicago Union Railroad in 1848 to the financial panic of 1857, during which time Chicago became the hub of the world’s largest railroad network;

3. the period that included the build-up to the American Civil War and the war that discusses its impact on Chicago;

4. the immediate post-war period up to the fire of October 8, 1871, in which occurred the construction of the first transcontinental railroad when Chicago, correspondingly became the largest and central city of the West, and;

5. the post-fire reconstruction between the 1871 fire and the July 14, 1874 fire, the result of which was the cancellation of all fire insurance policies by Nov 1, 1874, that finally instigated the eventual improvement of Chicago’s construction practices that occurred during the Chicago School of the 1880s.

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)