Following the death of John Kinzie in 1828, his heirs had established a pre-emptive claim in 1831 following the initial survey by James Thompson, to the 102 acres on the north side of the river in Section 10 where his house was located opposite Fort Dearborn. His younger son, Robert A. Kinzie, held a quarter interest in this land, even though his own store was on the west side. He had traveled to New York City during the winter of 1832-33 to order merchandise for his store for the upcoming season, where he offered to sell his share of his father’s property to a complete stranger who just happened to walk into the store at that precise moment. His name was Arthur Bronson, one of New York’s richest financiers, who had already heard the rumors about the region’s lush potential farmland.

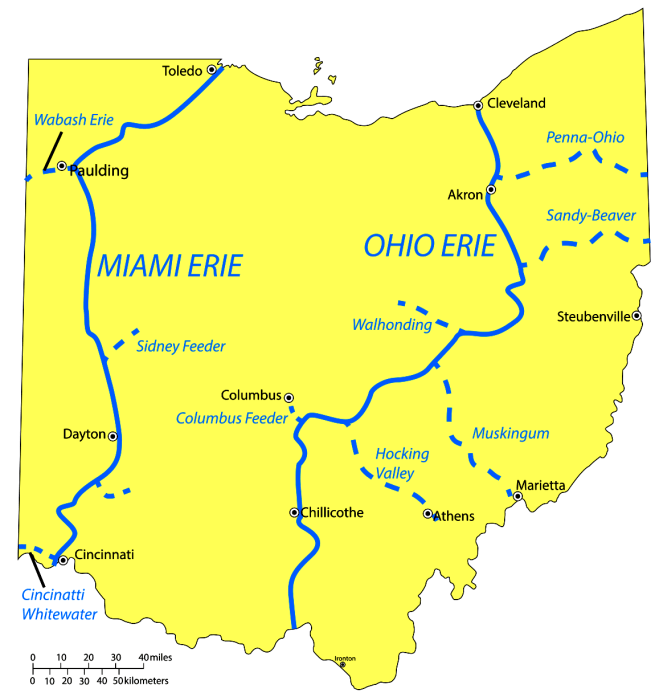

The Erie Canal had opened the vast plains of western New York to farmers who were eagerly clearing and cultivating the newly accessed lands. Unfortunately, the land that these farmers toiled over was owned not by them, but by three large land companies who had purchased this vast area from those who had been granted the original Dutch colonial land charters. The land companies were trying to sell the land to the farmers to recoup their investments, but the financial instrument in use at the time was an installment contract that allowed the farmer to pay annual installments towards the purchase price, but the land company held the deed until the last payment. As this was virgin land, the first years in which a farmer started to clear the land involved major start-up costs that meant there was little, if any profit with which to make the annual land payment. The companies were trying to be sympathetic to the realities faced by the farmers by approving the non-payments, but the contracts stipulated that any unpaid interest was to be converted to principal, which then compounded the interest due the following year. Therefore, as they tended their land year by year, they became more and more in debt, becoming virtually serfs to these companies. The result of this type of contract was that by 1829, over four years after the completion of the Erie Canal, not a single farmer in western New York owned the deed to the land that they had been working.

Charles Butler, a lawyer in Geneva, NY, had represented many of these farmers during these years, that had enabled him to develop a true sympathy for their plight. Butler was no mere backwoods attorney, but the younger brother of Benjamin Franklin Butler, the law partner of Martin Van Buren who in 1830 was the U.S. Secretary of State. The Butler brothers had been born and raised in Kinderhook, NY, that was Van Buren’s hometown as well. In fact, after finishing his law studies, Benjamin had clerked in Van Buren’s law office, and eventually became Van Buren’s right-hand man in the “Albany Regency” while the Senator was away in Washington. Butler’s younger brother, Charles, after having finished his pre-law education, had clerked first for his older brother in Van Buren’s law office, and then for Van Buren himself, becoming an intimate friend of Van Buren’s family during this period. The Butler brothers, Benjamin and Charles, in 1830, therefore, were close associates of Sec. of State Van Buren, who for all practical purposes was the third most powerful man in the U.S. government.

In early 1830, Charles had hit upon what at the time was a novel idea, but today is considered standard practice: to loan the farmers the money to buy the land using the value of the cultivated farmland as security for a mortgage. Being intimately connected with Albany politics, Charles was aware that a new company, New York Life Insurance and Trust had been chartered in January 1830 by Isaac Bronson, a commercial banker who was one of the wealthiest men in New York City at the time, and his older son, Arthur, to provide the mortgage service of which his clients were in disparate need. The Bronsons had intended the new company to be a more responsible investment alternative to the speculative investments that were quite common for the era, as they believed that commercial banks should be involved solely in investment loans. Butler’s civic mindedness took him to New York City to make his proposal to the Bronsons that seemed to fit their new business objectives perfectly. The Bronsons understood not only the value of Butler’s farmers’ cultivated farmland, but also of Butler’s intimate political and personal connections with Van Buren who ran Albany’s politics, and agreed to Butler’s plan, hiring him to be their mortgage application agent in Geneva County, where he was responsible for arranging over $1 million in mortgages over the next five years.

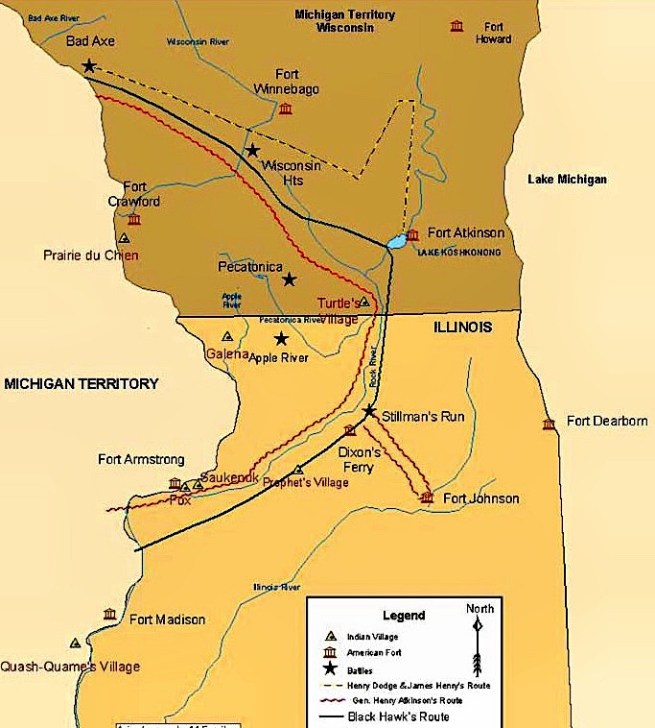

Some three years later in late 1832, Arthur Bronson had begun to hear of the stories about the Illinois territory from the soldiers returning from the Black Hawk War. Bronson, who was an acquaintance of General Scott, sought out his recommendation about the area who confided that Chicago’s location would be very important in the future settlement of the West, no doubt confirming Bronson’s intuition. In January 1833, while Butler was in New York City on regular business, Bronson broached the idea to his trusted mortgage agent that the two of them make a trip to Chicago that summer to evaluate the investment potential of the region. Butler’s political value to Bronson had since increased with the 1832 Presidential election that resulted in the re-election of Pres. Jackson and saw Butler’s good friend Martin Van Buren elevated as Jackson’s Vice-President over the incumbent John C. Calhoun with a corresponding promising future for Butler and his brother as well.

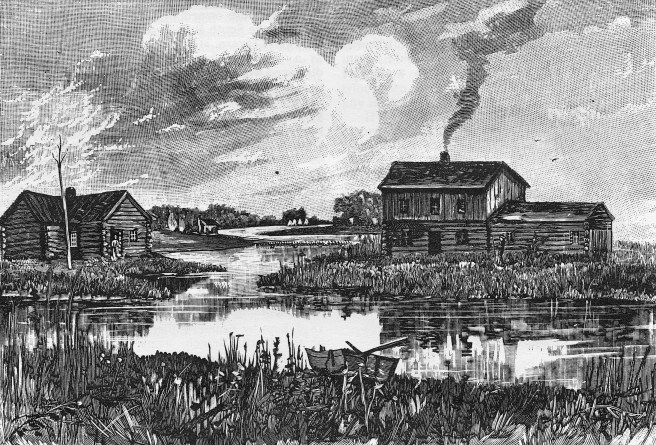

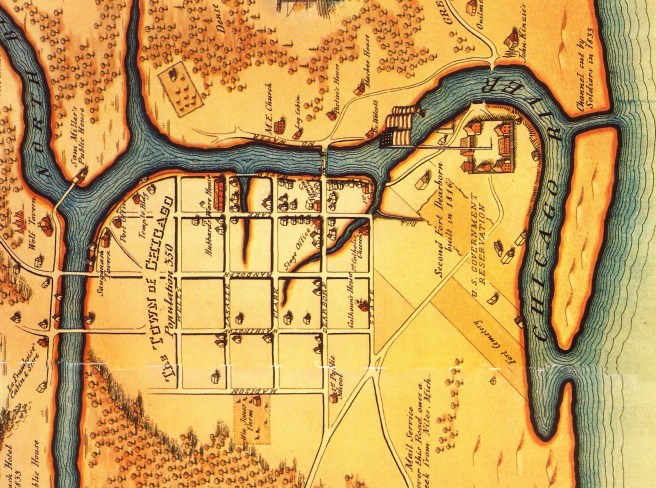

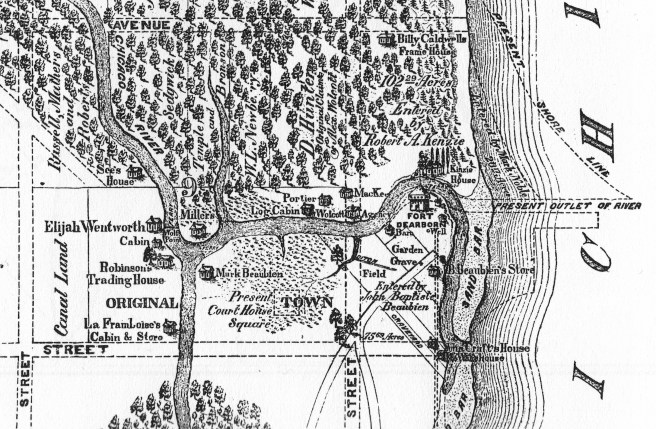

Only days after Bronson had suggested the trip to Butler, he was walking around New York City gathering information and chanced to visit the store of a supplier to Native traders, where he encountered Robert Kinzie, who made the offer to Bronson to sell his portion of his father’s land on the north side of the Chicago River if he was interested in the land when he saw it during his upcoming trip to Chicago. Bronson and Butler departed on their journey in June 1833, and arrived at Chicago on August 2, only days before the local election that determined whether or not to incorporate the settlement as a town, to inspect the potential of the area and found:

“The present condition and prospects of Chicago… was, of course, the subject of constant and exciting discussion. At this time, that vast country lying between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi River and the country lying northwest of it,… lay in one great unoccupied expanse of beautiful land… beautiful to look at in its virgin state, and ready for the plow of the farmer. One could not fail to be greatly impressed with this scene,… and to see there the germ of the future, when these vast plains would be occupied and cultivated, yielding their abundant products of human food, and sustaining millions in population. Lake Michigan lay there,… and it is clear to my mind that the productions of the vast country lying west and northwest of it on their way to the Eastern market… would necessarily be tributary to Chicago, in the site of which… the experienced observer saw the germ of a city, destined from its peculiar position near the head of the lake and its remarkable harbor formed by the river, to become the largest inland commercial emporium in the United States.”

It is important to point out that Bronson and Butler were not fly-by-night land speculators, but conservative, professional investment businessmen who had played pivotal roles in the economic success in western New York State that had been made possible with the construction of the Erie Canal. They were builders as much as they were investors.

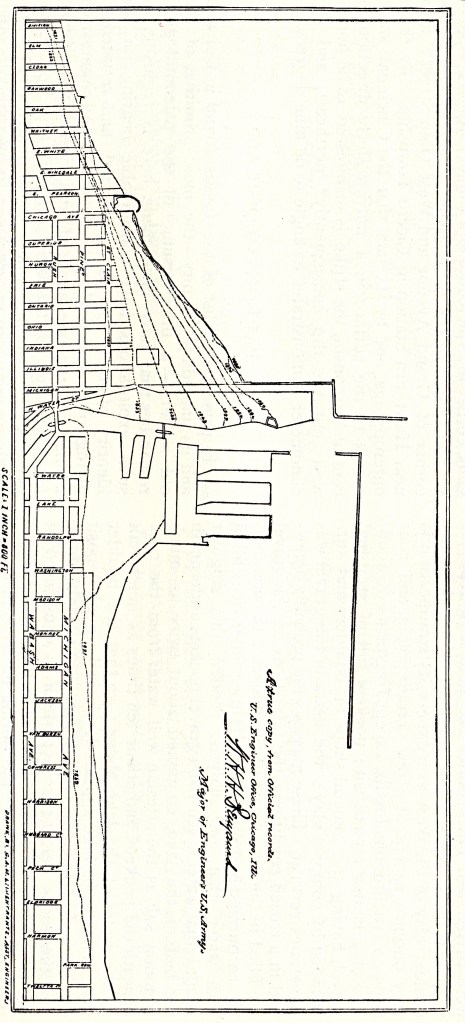

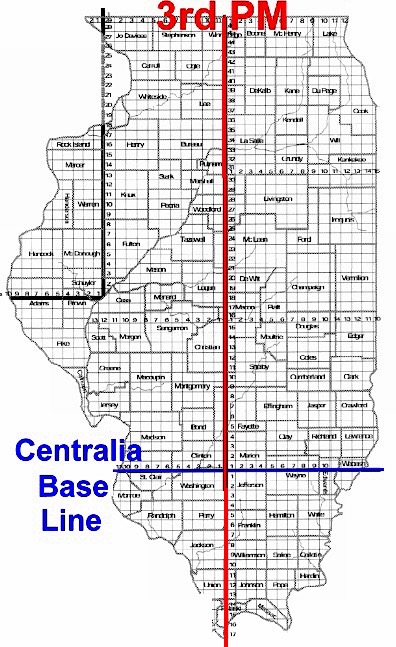

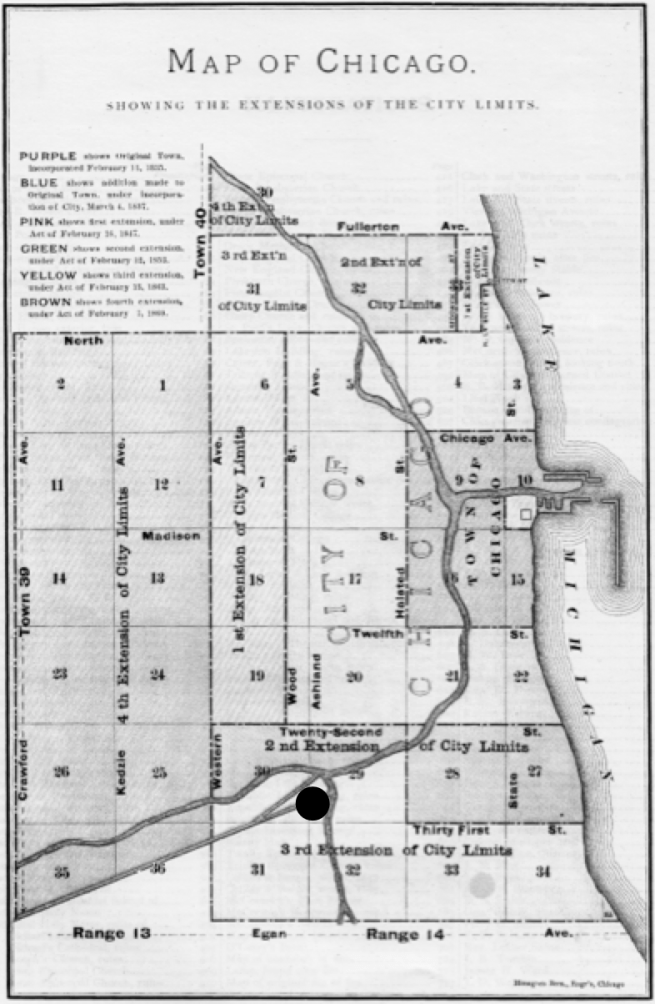

They inspected the Kinzie property, the northern portion of Section 10, bounded by the lake on the east, the river on the south, State Street on the west and Chicago Avenue on the north, but Bronson declined to purchase Kinzie’s quarter interest at this time because other parties still held a majority interest in the property. Kinzie’s brother-in-law, Major David Hunter, not only held one-half interest in this property, but also owned 80 acres immediately adjacent to the west in Section 9, known as Wolcott’s (Dr. Alexander Wolcott had been the Indian Agent from 1820 to 1830) addition bounded by State Street on the east, Kinzie on the south, La Salle on the west, and Chicago on the north. Bronson did eventually buy all of Hunter’s property, 182 acres along the northern bank of the river’s mouth, for $20,000 on Nov. 1, 1834, and hired local resident Walter L. Newberry to be his land agent. Newberry was the younger brother Oliver Newberry, a wealthy Great Lakes shipping and Native supplies merchant from Detroit, who had sent George W. Dole to Chicago in 1831 to open and manage a store there. Newberry had then sent his brother, Walter, to assist Dole in their company’s growing business.

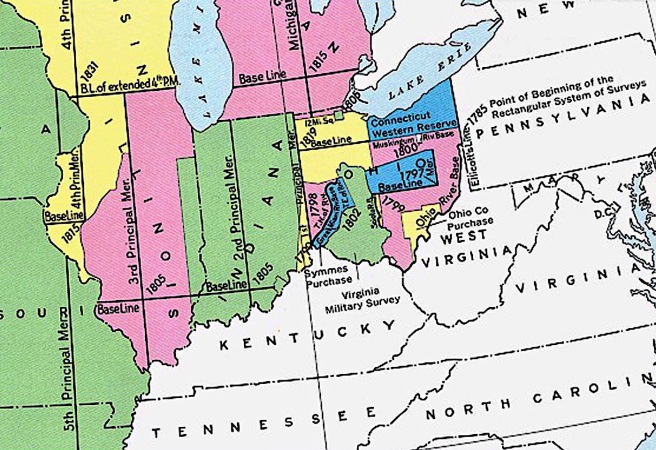

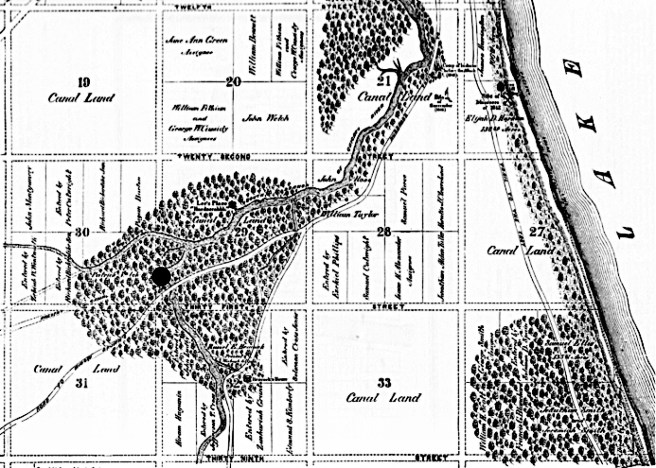

Meanwhile, the 1833 land boom had become an explosion in October when the land in the School Section, Section 16, immediately to the south of Thompson’s original platted Section 9, that is bordered by Madison on the north, State on the east, Halsted on the west, and Twelfth (now Roosevelt) on the south, was put up for sale at public auction, bringing in a sum of $38,865. An even greater investment potential, however, was about to become available immediately to the west of Chicago. On September 26, 1833, the United Nation of Chippewa, Ottawa, and Pottawatomie Tribes had signed a treaty in Chicago that ceded to the Federal government all of their remaining lands east of the Mississippi River. In exchange for the government’s promise to pay their living expenses for one year and $1 million for miscellaneous settlements, the Tribes had promised to move west of the Mississippi River within three years. This action extinguished the last Native claim in northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin, and opened the area for white settlement, in which the government planned to start selling lots in May 1835. However, the ultimate removal of the Natives from Illinois also meant the end of the lucrative Native and fur trade that had sustained the area’s economy since its discovery by Europeans. This economic loss would be more than offset in the immediate future, however, by the greater commercial potential in the sales of the newly vacated Tribal lands.

Upon their arrival the two visitors from the East were quickly approached by Chicago’s leading businessmen regarding their recommendations concerning the funding and construction of the canal. Perceiving that the commercial potential of the region revolved around the completion of the canal, Bronson, who had witnessed the construction of the Erie Canal and understood the potential profit to be gained not only in building the canal, but more importantly, also in speculating in the land immediately adjacent to this new capital improvement, shrewdly purchased 7,000 acres of land adjoining Canalport (its name was changed later to Bridgeport). At this time support for the canal was still languishing in the Illinois legislature as there were those who were still arguing for a railroad over a canal, so the two New Yorkers provided appropriate assistance the following year in the presentation of a petition to the legislature that requested the incorporation of a new company to construct the canal. The presentation of the Chicago canal petition in the General Assembly on November 5, 1834, reinforced the efforts of newly elected Governor Duncan, who was from northern Illinois and, fearing the potential monopoly of a railroad, was also an advocate of the canal.

FURTHER READING:

Andreas, Alfred T. History of Chicago, 3 vols. Chicago, 1884-1886. Reprint, New York: Arno Press, 1975.

Bernstein, Peter L. Wedding of the Waters: the Erie Canal and the Making of a Great Nation” New York: Norton, 2005.

Haeger, John Denis, “Eastern Financiers and Institutional Change: The Origins of the New York Life Insurance and Trust Company and the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company,” The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 39, No. 1, (March 1979), pp. 259-273.

Harpster, Jack. A Biography of William B. Ogden. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University, 2009.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Pierce, Bessie Louis. A History of Chicago-1. New York: Knopf. 1940.

Stoddard, Francis Hovey, The Life and Letters of Charles Butler, New York: Scribner: 1903.

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)