1839 saw the end of Cincinnati’s antebellum hopes to have a direct railroad link to the Atlantic. While Robert Young Hayne, the President of the LC&C had used the momentum from its 1836 Convention in Knoxville to reach the minimum of $4 million in stock subscriptions by November 1836 mandated by its charter in order to incorporate by 1837, he was engaged in an intense battle over the railroad’s actual route with, who at first might seem an unlikely opponent to Hayne’s South Carolina railroad, the state’s U. S. Senator, John C. Calhoun. Calhoun actually owed his current seat in the Senate to Hayne, who had graciously resigned his seat so that Calhoun could return to the Senate following his resignation as Andrew Jackson’s Vice-President following the 1832 Presidential election in which Van Buren had been nominated and elected to replace him. Calhoun’s recalcintrance to the LC&C was not aimed at Hayne, but rather was a result of his conscious effort in which he was involved in at the time to remake himself and his political values to be more in alignment with his constituents. In essence, Calhoun’s political career was a microcosm of how the antebellum South had evolved following the War of 1812.

After having given his best in strengthening the War Department and doing all he could to support Monroe’s nationalist agenda during those eight years, Calhoun, who was elected Vice-President in 1824, was disappointed by not being elected President and had returned to his South Carolina home early in 1825 to reevaluate his politics before he was to be sworn in as Adams’ Vice-President. During these last seven years, the country’s politics had changed, and even more important to his long-term political career, the politics of his home state had radically changed while he had been in Washington. The sense of relief throughout the country following the passage of the Missouri Compromise in 1820 had been short-lived, especially among whites in South Carolina due to the Denmark Vesey affair. Vesey was a former African-American slave who had bought his freedom around 1799 in Charleston, where he had become a leading member of the city’s African-American community. Encouraged by the anti-slavery talk elicited during the Congressional debate over the Missouri Compromise, Vesey apparently hatched a plan for “the uprising,” a revolt by the town’s slaves that involved taking over the city’s armory, killing as many whites before commandeering ships in the harbor and sailing to the free-black republic of Haiti. Vesey had originally scheduled the revolt to begin on Bastille Day, July 14, 1822, to evoke the French Revolution, but two slaves who did not support the plan reported it to city officials in June who quickly arrested Vesey and any suspected accomplices. Vesey and three others were hanged on July 2, 1822, after having been given little, if any legal advice or hearings. The city’s actions were controversial among the country’s legal experts, but they assuaged the immediate fear of the city’s white citizens, who at the time were in the minority of the city’s population.

Then on May 22, 1824, Congress enacted a tariff on manufactured goods to protect nascent American industries, primarily in the North, from cheaper British goods. The tariff was the first of three to pit the interests of Northern industrialists against Southern growers, who now enjoyed none of the protection of the tariff but were forced to pay the higher prices for industrial goods. The effects of the tariff were just begining to be felt in 1825 when the price of cotton plunged forty percent, brought on by the additional supplies of cotton coming from the newly-established plantations in Alabama and Missisissippi. Therefore, at the time of Calhoun’s election as Vice-President, South Carolina had fallen under the influence of its political “Radicals” who had little interest in Calhoun’s prior commitment to nationalism that argued for the necessity to protect the country’s industries with tariffs and to moderate reconciliation on the slavery issue. As he traveled around his home state following his election, this change was abundantly clear to him, and he realized that if he was ever to achieve his presidential ambitions, he needed to first secure the support of South Carolina’s voters by realigning his political views with those whose votes he needed. Thus had emerged in 1825 the John C. Calhoun that the history books record as the Sectionalist who was the champion of Southern state’s rights as he returned to Washington as Adams’ Vice-President.

He grew increasing combative with Adams over the President’s proposed internal improvement programs, eventually accepting a deal with Andrew Jackson, negotiated by none other than the wily Martin Van Buren, who had his own political agenda in blocking DeWitt Clinton’s ambition to be Jackson’s running mate (that ended with Clinton’s death on Feb. 11, 1828), to be Jackson’s Vice President in 1828, thereby informally politically abandoning Adams, his President. In an attempt to seal the election for Jackson, Calhoun, in league with a number of Southern Senators, concocted a scheme now referred to as the Tariff of Abominations, that so increased the cost of tariffs across the board that even Northerners would vote against it, gving the Southerners an election issue. To their chagrin, the plan had backfired because there were sufficient Northerns who saw the tariff as an opportunity to protect the country’s (albeit the majority were in the North) businesses and passed it on May 19, 1828, leaving the South with higher prices to pay for almost all of their imported goods.

Nonetheless, Jackson handily defeated Adams’ bid for reelection in 1828 with Calhoun continuing as the Vice-President. While Calhoun’s revised political views would succeed in having him reelected to the Senate for the remainder of his life, they often ran counter to those of Jackson, especially when the two came into conflict over Nullification, the issue of whether or not a state had the right not to enforce a federal law, such as the 1828 Tariff. Calhoun had defended this theory, following the election, in his pamphlet, The South Carolina Exposition and Protest that he anonymously published in December 1828, assuming that Jackson upon assuming office would simply support the repeal of the tariff. Jackson, however, had no such plans and with the able assistance of the ambitious Van Buren would see to it that Calhoun would never be a Presidential candidate, starting with his selection of Van Buren, and not Calhoun, to be his Vice-President candidate in his upcoming reelection campaign of 1832. South Carolina held a state convention immediately after the election on Nov. 24, 1832, in which it voted that it had the right to refuse to enforce the U.S. tariff, beginning on Feb. 1, 1833. Meanwhile, Hayne had been elected as South Carolina’s Governor, leaving his U.S. Senate seat vacate. The embittered Calhoun resigned as Vice-President before Van Buren could be inaugurated as his replacement. The South Carolina legislature then promptly elected Calhoun to fill Hayne’s remaining Senate term so that he could return to the national stage to better defend South Carolina’s rights.

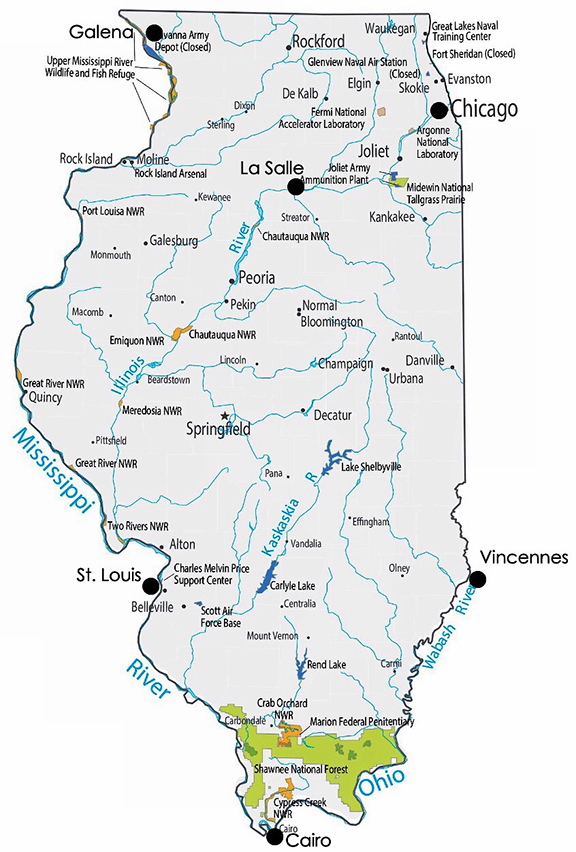

This was the embittered Calhoun that was now fighting Hayne’s planned route to Cincinnati through South Carolina. Calhoun was initially in favor of the proposal to build a railroad to Cincinnati, but he wanted a route within the state different from the one Hayne was in the process of surveying at the time. Hayne was looking out for the commercial interests of Charleston’s port and, therefore, was pursuing a route through the center of the state, hoping to divert agricultural products away from the Savannah River that flowed to Savannah’s port (in Georgia). Calhoun’s plantation, Fort Hill, however, was located in the far northwest corner of South Carolina, near the Savannah River, and it would be to his obvious advantage if the railroad’s planned route would be as close as possible to make it easier to ship his plantation’s cotton to Charleston. Hayne’s standing among his stockholder’s was sufficient for him to overcome Calhoun’s campaign and contracts for the first leg of the new route from Columbia, the state capital, to the C&H’s station in Branchville were signed and the start of construction was celebrated in Columbia with the traditional parade and speeches in March 1838. As the national economy continued to sour, however, Charleston suffered a devasting fire on April 27-8, 1838, that destroyed over 1000 buildings and 25% of the city’s business district that totalled over $3 million in property, leaving some of the railroad’s investors bankrupt. Hayne did all he could do to keep the construction on schedule, but this effort completely exhausted him and he died from “bilious fever” at the age of 48 on September 25, 1839. This was all Calhoun needed to succeed in rerouting the South’s first attempt to build a railroad to the Mississippi basin away from the NorthWest to the SouthWest at either Memphis or New Orleans, “Thus ends the humbug with a debt of several millions on the state, great loss to those concerned, and the loss of credit and mortifcation to the projectors,” crowed Calhoun. While the route between Columbia and Branchville was eventually completed by 1842, Calhoun’s surrogate, James Gadsden was elected President of the company in September 1840, who changed the company’s name (to the South Carolina Railroad) and its goal from linking Charleston to the NorthWest at Cincinnati to one that consolidated railroad traffic within the state. Having killed the potential link between the South and the NorthWest, Calhoun now focused on championing an all-southern route between the Atlantic and the Mississippi River at Memphis to keep as much investment within the region, and out of the hands of Northerners. With the premature death of Hayne and Calhoun’s subsequent rerouting of the South Carilina Railroad, Dr, Drake’s dream of Cincinnati’s continued growth as it became the hub between the Southeast and the NorthWest never materialized. The “rehabilitated” John C. Calhoun would make sure that the South and NorthWest would never be connected with a railroad, leaving the future of the route of a railroad connecting the country open to Chicago.

FURTHER READING:

Grant, H. Roger. The Louisville, Cincinnati, & Charleston Rail Road. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014.

Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Henry Clay- The Essential American. New York: Random House, 2011.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

(If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to eMail me at: thearchitectureprofessor@gmail.com)